Why This Matters: A Climate Crisis Meets Urban Poverty

Bangladesh—one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries—is experiencing a dramatic influx of climate migrants from rural areas. Many settle in Khulna's slums like Bastuhara (1,628 households) and Rupshar Char (1,157 households), where:

89% of Khulna slum households face seasonal water scarcity due to climate-induced groundwater depletion.

Only 6–10 liters of water are used daily by nearly half the population—far below the minimum human requirement.

Nearly 40% of water at point-of-use is contaminated with fecal coliform, putting lives at risk.

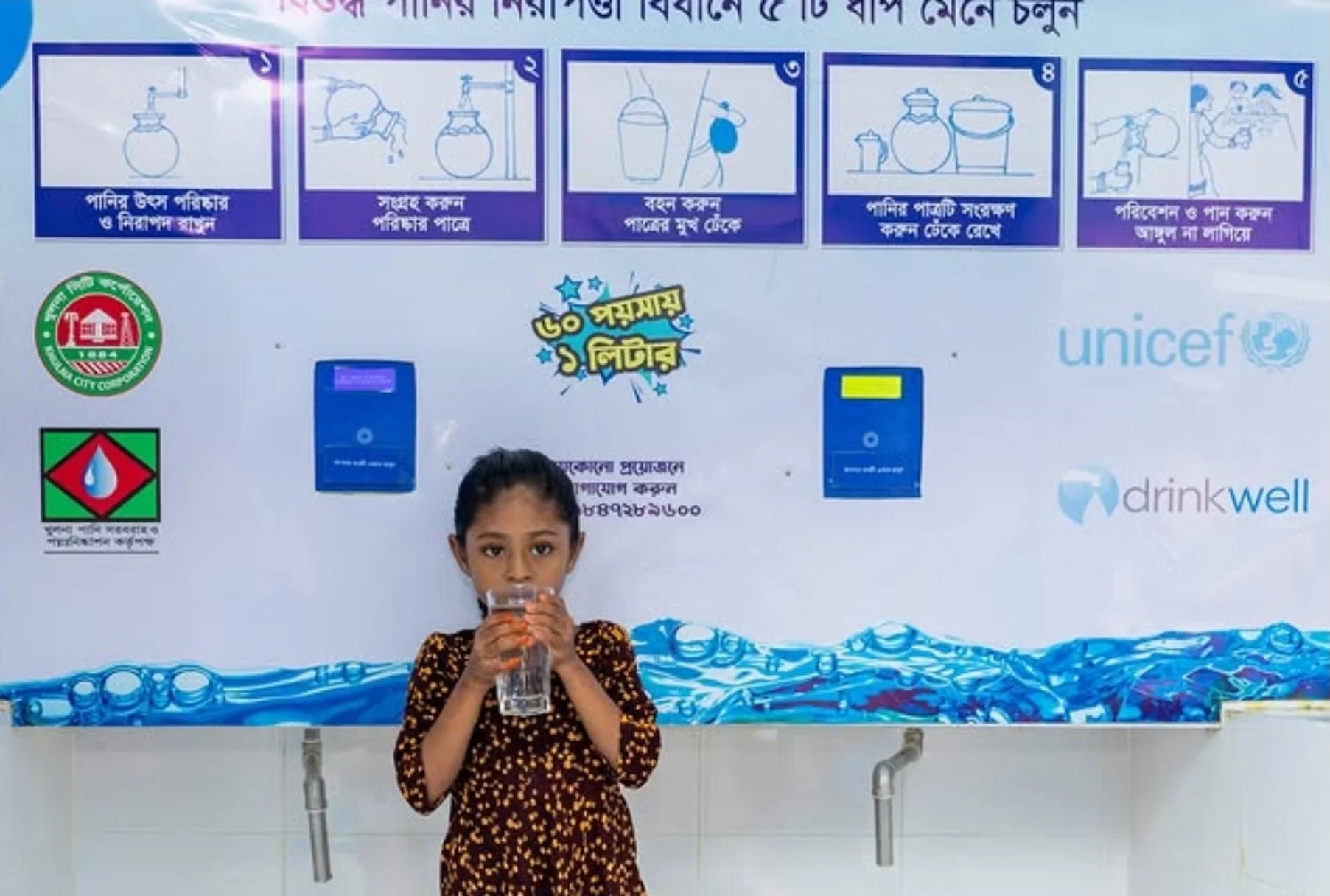

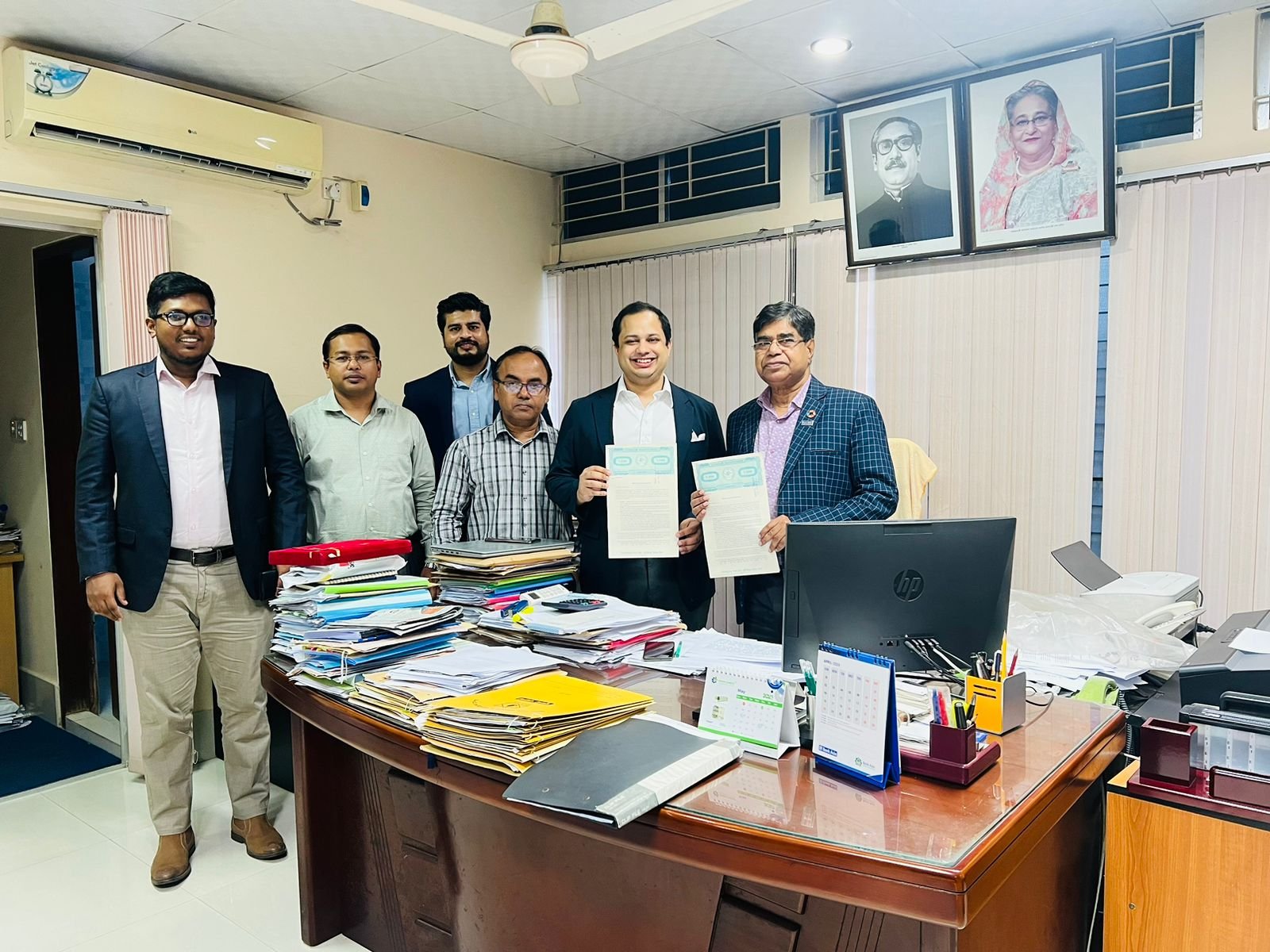

Drinkwell, in partnership with UNICEF Bangladesh, Khulna WASA, and the Khulna City Corporation (KCC), proudly inaugurated two climate-resilient Water ATMs on July 1, 2025—located at Bastuhara Colony Bazar and Rupsha Natun Bazar Char Masjid. In Khulna:

“This isn't just about water—it's about restoring dignity, resilience, and rights to climate-affected families who’ve long been left behind.” — Minhaj Chowdhury, CEO, Drinkwell

The Drinkwell Solution: Technology + Equity

The newly launched Water ATMs are piloting a cross-subsidy social business model that combines several innovative elements:

Cross-subsidized Tariff Model: Developing a cross-subsidy business model that will ensure the long-term operation and maintenance of the ATMs, with UNICEF providing initial capital expenditure and two years of operational costs. The goal is for the system to become self-sustaining and expand over time to cover entire slum communities. The cross-subsidy model guarantees free water to at least 100 ultra poor households (100*20 = 2000 L/day) with the assumption that sufficient low to middle-income households will pay a marginally higher tariff to offset the loss of revenue from the free water being provided to the ultra-poor.

Advanced Treatment Facilities: Ensuring the highest standards of water quality, free from contaminants like fecal coliform.

Inclusive Design: Water ATMs are designed to be accessible for everyone, including individuals with disabilities and children.

Community Empowerment: Raising awareness among 2,785 households about the benefits of safe water and the Water ATM technology, aiming for a 70-80% conversion rate to ATM cardholders.

Emergency Protocols: Recognizing Khulna's vulnerability, the business plan includes robust emergency protocols to ensure water access even during disasters.

Behavior Change Workshops: Training for women, youth, and climate migrants on water hygiene

These Water ATMs provide safe, year-round, contamination-free water within walking distance for slum residents—an essential safeguard as groundwater depletion and infrastructure collapse become more frequent under climate stress.

Impact Targets

✅ 2,785+ low-income households gain reliable safe water

✅ 100+ ultra-poor families receive free daily water

✅ Significant reduction in waterborne illnesses such as cholera, dysentery, jaundice

✅ Women and girls save time collecting water—reclaiming hours every day